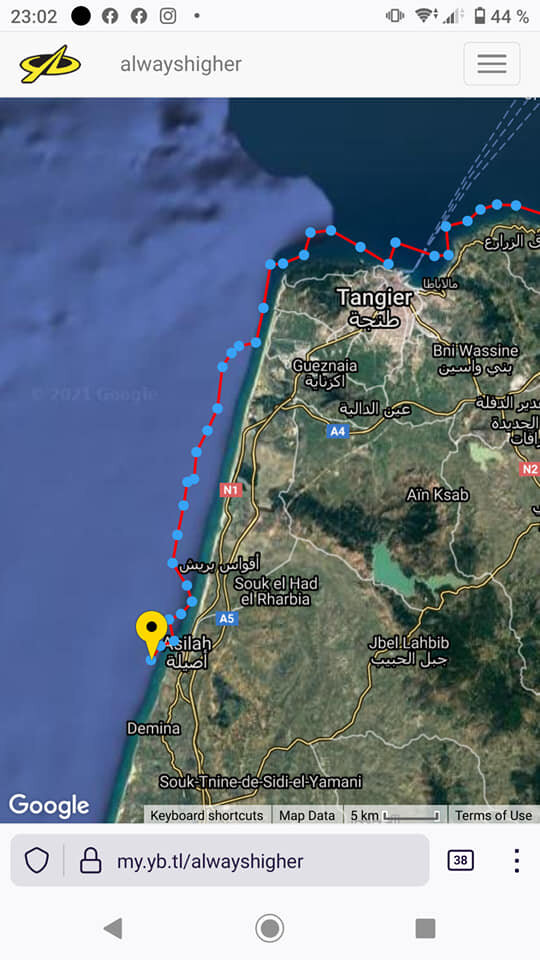

Note: Two months ago (January 2025), I found out that the distance I covered in 12 hours was actually a record, surpassing the previous one by a few miles.

I set off for my first attempt as planned on the 29th at 10:40 AM, leaving the beach at 10:20 AM in front of Dalia Beach. The support boat, Gladius, had departed from Mohammedia the day before and reached my location at 10 AM. After wrapping up my final preparations on the beach, surrounded by my closest people, I met them in the bay. I was handed a radar reflector, a few small torches, and a VHF radio.

It was my first time meeting the crew—they had volunteered upon hearing about my record attempt. We had a brief discussion on how to proceed once we reached open water, and then, we left that beautiful bay behind.

The weather and the swell: The forecast predicted 9-knot winds, but reality had other plans. Shortly after setting off, I realized the conditions were far more chaotic. While the dominant swell came from the west, waves were hitting me from every direction—east, left, right, everywhere. The real challenge was avoiding a nose dive. Imagine surfing a 5-to-6-foot wave, only to be met with another 5-foot wave crashing straight at you.

I had two 5-liter water containers and a bag holding my food and batteries—about 7 kilos in total—making it difficult to keep the boat balanced. The wind was gusty, hitting 15 to 20 knots at times, forcing me to stay hyper-focused. Not only did I have to track those unpredictable waves, but I also had to watch my back for gusts, ready to adjust both my mainsail and route in an instant.

The swell was short-period and hollow. The only way to surf it properly was by giving a quick “kick” to the mainsail when the boat picked up speed. This technique—done with a sharp pull—lifts the bow and accelerates the boat forward. But it wasn’t just about sail handling; my body had to follow. Every movement required precise counterbalance to avoid a “counter heel” situation. A capsize in those conditions wouldn’t just mean getting wet—it would mean a long, exhausting swim, with the boat flipping completely upside down. In the Strait, that kind of mistake is unforgiving. I fought for seven relentless hours just to break free.

Breaking Out of the Strait

Going downwind was impossible, so I had to force my way out of the Strait on a close reach. I couldn’t afford to open my angle more—staying tight gave me a better chance of avoiding a counter-heel capsize. Every time I felt the boat tipping to my side, I pushed the rudder and got into tacking position.

When facing the Moroccan coast, my angle was 90 degrees, but when heading toward Spain, I had a slightly more open course, allowing me to go deeper only on one tack—starboard. On port, I was sailing crosswind; on starboard, I was reaching.

At one point, I crossed paths with a supertanker. I didn’t panic—just watched in awe as waves crashed against its hull with immense force. These ships move fast. You spot one two kilometers away, and in minutes, it’s towering beside you.

I kept pushing forward until I reached Cap Malabata, where I slipped into Tangier Bay for a moment—just to take a deep breath and have some tobacco. I had never experienced anything like this. I was proud of myself and relieved that I hadn’t capsized.

Every tack required shifting all my weight—moving those two big water bottles from one side to the other. It was anything but a smooth maneuver. From Cap Malabata to Cap Spartel, the swell lengthened slightly, but the wind remained strong.

I rounded Cap Spartel just before dark. The water flattened—it felt like a massage after everything I’d endured. The expected 40 km crossing had stretched to 65 km by the time I reached Cap Malabata from Cires Point.

By 6 PM, I was in the Atlantic. The wind eased for an hour, giving me a brief break. But as soon as the sky turned as dark as black coffee, the wind returned—this time from behind. It felt like it was chasing me. I had hoped that, in the Atlantic, I would finally get a proper side wind… but no.

Pushing Through the Final Hours

Before nightfall, I had a quick talk with the support boat, and we set off again. By 10 PM, we had lost sight of each other. Around 1 AM, exhaustion hit me hard—I started feeling weak, threw up, and felt feverish. An hour later, I capsized. Getting the boat back upright drained the last of my strength. The cold seeped into my bones, and I knew I had to find shelter.

Asilah’s port was my best option, but finding the entrance was another challenge. The marina was under construction—no lights, no clear way in. I spotted a fisherman, asked for directions, and he pointed toward a resort with blue lights, telling me the entrance was near it. At 100 meters out, the wind completely died. I paddled for 30 minutes, using the swell to help me in, careful not to get dragged onto the jetty.

I made it to the authorities’ pier. They were as surprised to see me as I was to be there. Apparently, they had been tracking me with thermal binoculars, trying to figure out what I was doing and who I was. By 5 AM, I called my brother, asking him to bring my documents and phone. The officers welcomed me with a hot shower, food, a blanket, and a place to rest. True hospitality.

My brother arrived with dry clothes, and I arranged for transport to pick up the boat. By 9 AM, my wife and my friend Fabrizio showed up. We headed back to Tangier, where I finally sat down with a hot drink—and immediately passed out for a few hours.

The Journey of a Lifetime

This experience will stay with me forever. The Strait tested me like nothing else—deep focus, maximum effort, towering waves, dolphins gliding beside me, massive birds curiously circling overhead. A battle with the elements that I wouldn’t trade for anything.

Next time, I’ll probably start from Tangier instead of Point Cires. My hands were shredded from never locking the mainsheet through the entire crossing. But I learned. I pushed my limits. I walked away with an even greater love and respect for the ocean—and for sailing itself.

End of story.

Huge thanks to my sponsors for taking a chance on this madness. To the team on Gladius, who volunteered to support me through hell and back—you have my deepest gratitude. To my friends, my family, the Moroccan Sailing Association, my wife, and my brother Karim—thank you.